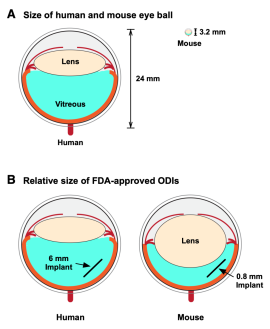

Palo Alto, CA — In the operating room and clinic, Vinit Mahajan M.D., Ph.D., Stanford Ophthalmology vice chair for research and ChEM-H fellow, uses ocular drug implants (ODIs) to safely deliver steroids into the eye to treat a range of eye diseases including uveitis and diabetic retinopathy. Mahajan surgically injects the drug implant directly into a patient’s vitreous fluid. The slow, sustained release ensures drugs reach the retina for months to years. The localized drug reduces systemic toxicities that might come from a pill or intravenous injection. Mahajan’s research team has now developed a method to expand the use of ocular drug implants in mouse models of human eye disease.

Mahajan knew that drug implants in mice would be an excellent way to test the efficacy and toxicity of new and repurposed small molecule drugs. An implant’s controlled drug release would overcome the problem of the short half life and fast clearance of small molecules that otherwise rapidly leak out of the eye.

But there was no injection tool or method available for animals with such small eyes. This left a vast library of small molecule therapeutics untapped.

Mahajan said, “There has been a critical disconnect between medicinal chemistry and retinal disease. We have identified numerous mouse models of human eye disease; and there is a revolution in designing small molecule drugs. Because of technical reasons, the two have not been integrated.”

Testing drugs in mice is a crucial step in bringing new therapies from the laboratory into the clinic. Mice are invaluable for understanding eye disease and the process of drug development because they are biologically similar to humans, suffer from many of the same diseases, and can be genetically manipulated to mimic almost any human disease. Mice also serve as one of the most cost-efficient preclinical models for testing drugs. Eye researchers have not been able to tap into the wealth of information mice can give them about drug therapies because mouse eyes are only two millimeters long.

Mahajan said, “We can use existing implant injection methods on animals with bigger eyes, but the lack of disease models in these animals limits research opportunities. We can’t use these animals to test for drug efficacy. We can really only use them to test toxicity.”

Postdoctoral fellow Young Joo Sun Ph.D. assembled a collaborative team within the ophthalmology department to take on the challenge of developing a microscopic implant that could be injected into mouse eyes. Sui Wang Ph.D., assistant professor of ophthalmology, and her postdoctoral fellow Cheng-Hui Lin Ph.D. met with the Mahajan lab and worked out some concepts.

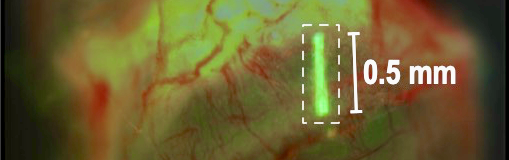

After tinkering with various materials and surgical methods, a cost-effective, minimally invasive intravitreal implant injection method for mouse eyes was developed. The 0.5 mm implant was molded from an inert chemical, PGLA, and looked like a tiny white thread under the microscope. Custom injection needles were fashioned from microcapillary glass tubes.

Eventually, the team created two methods for injecting implants: an air-pressure-based injection and a plunger-based injection.

Young Joo said, “You have to have good, steady hands, and Cheng-Hui is a master of mouse eye surgery.”

“We named our method ‘MI3’ for ‘Mouse Implant Intravitreal Injection’”, Cheng-Hui said. “After the injection, we monitored the mice for any damage or toxicity for several months and found the injection was safe. The eye healed nicely, there was no rejection of the implant, and we could still image the retinal structure and the eye.”

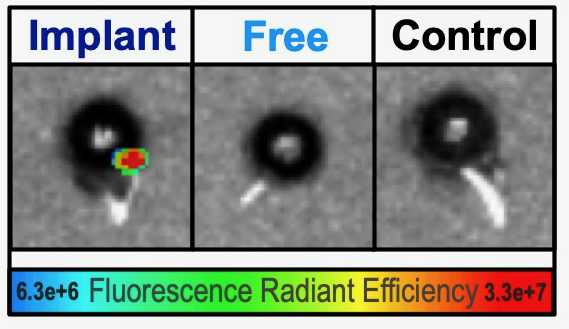

Next, Soo Hyeon Lee Ph.D., group leader in the Mahajan lab, tested whether a drug would last longer in the eye. She utilized a fluorescent small molecule drug and mixed it with the implant.

Soo Hyeon said, “While an injection of the fluorescent drug “glowed” for only a few hours, the drug mixed into the implant lasted for days inside the mouse eye.”

Implants that release drugs in a slow, sustained manner have advantages other than being absorbed directly into the eye. For patients with chronic eye diseases, they can reduce the number of clinic visits and provide a controlled drug dose that is not reliant on patient behavior.

Young Joo added, “This ocular implant testing platform is a great way to test new drugs, but it also lets us go back to old drugs that cleared the eye too quickly to be effective. Being able to release drugs slowly so that they are absorbed in the eye could be a game changer for drugs that failed to treat eye diseases in the past.”

Even though the drug-release profile of microscale implants is not directly transferable to that of millimeter-sized human implants, their data profile on efficacy and toxicity of a sustained drug release can serve as a reference when developing human ocular implants.

Sui said, “The beauty of this method is that it can be replicated in any lab using our step-by-step protocol along with the surgical video. Labs that have performed gene therapy testing in mice should be able to easily adapt their protocols to now test small molecule drugs.”

One mission of the Mahajan lab is to use next-generation molecular biomarkers of health and disease to identify eye diseases before they begin and select the best therapies for each unique patient. When a therapy is lacking or does not exist, they strive to develop one in the laboratory. The mouse implant injection method will help them meet their mission.

“There are hundreds of mouse models with eye diseases. Being able to implant sustained-release drugs into the eyes of these mice opens up an entirely new avenue for therapeutic development,” Mahajan said.

The manuscript, “Intravitreal implant injection method for mouse eyes”, was published in Cell Reports Methods: Sun et al., 2021, Cell Reports Methods 1, 100125. Co-authors include: Young Joo Sun, Cheng-Hui Lin, Man-Ru Wu, Soo Hyeon Lee, Jing Yang, Caitlin R. Kunchur, Elena M. Mujica, Bryce Chiang, Young Soo Jung, Sui Wang, and Vinit B. Mahajan.

Funding/Support: VBM is supported by NIH grants (R01EY026682, R01EY024665, R01EY025225, R01EY024698, and P30EY026877), Stanford ChEM-H IMA, and Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, New York. SW is supported by American Diabetes Association (1-16-INI-16) and P30 to Stanford Ophthalmology.