Palo Alto, CA — Is there something to feed retinal cells that can give them the energy to withstand gene mutations that make them sick? This is a question that Vinit Mahajan M.D., Ph.D., professor of ophthalmology at Stanford University, and his colleagues have been asking in the hope of finding widely applicable therapies for patients with genetic eye disease. Their recent study suggests a breakthrough.

Mahajan said, “Gene therapy for retinal disease is a reality today, but it only works for those patients with a few, very specific genes.”

Gene therapy for genetic eye disease is approved for one gene and under investigation for another ten or so genes, but such treatments have their limits. Gene therapy is expensive and specific to a single gene. With nearly three-hundred genes linked to retinal disease, it may not be possible to create a gene therapy for each one.

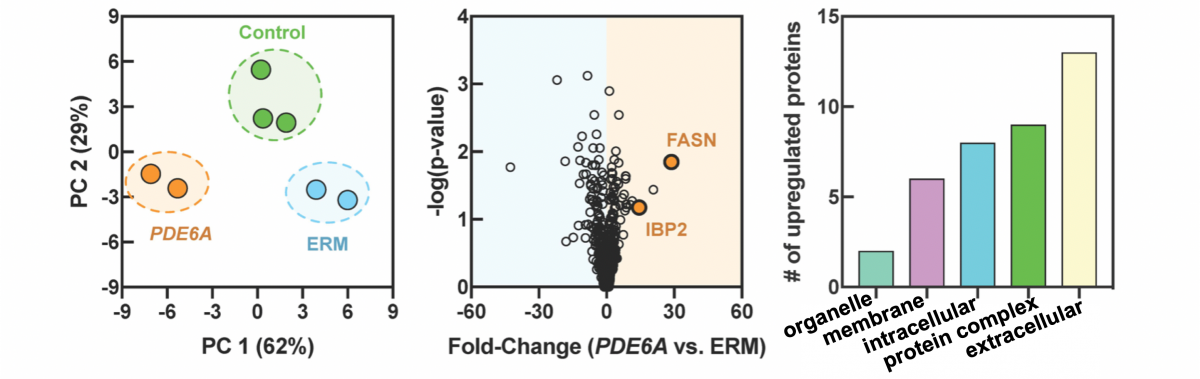

To identify other therapeutic targets, Mahajan’s research team used proteomics, the large-scale study of proteins, to identify molecules that change when the retina degenerates. After collecting eye fluid biopsies from humans and mice with retinitis pigmentosa, lab members measured the levels of thousands of proteins in the fluid.

For over ten years, Mahajan has been using proteomics as a sophisticated, efficient method to understand eye disease with personalized results that can lead to novel treatments.

In retinitis pigmentosa, Mahajan’s team identified groups of proteins affected at the onset of photoreceptor death. They noticed that specific molecular pathways that support cell energy were lost very early. They hypothesized that if they could replace the energy molecules, it might stop the degeneration.

Mice with retinitis pigmentosa were treated with various dietary interventions, including a ketogenic diet and metabolites involved in fatty-acid synthesis, oxidative phosphorylation, and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle.

They noticed a significant rescue effect in mice with dietary supplementation of a single metabolite, ɑ-ketoglutarate. State-of-the-art metabolomic analysis of mouse retinas showed that replenishing TCA cycle metabolites via oral supplementation prolonged retinal function and provided a neuroprotective effect on the photoreceptor cells and inner retinal network.

Mahajan said, “Its remarkable that a simple dietary molecule could delay the retina degeneration without specifically targeting the causative gene. Although this did not cure the gene mutation, in many patients, just delaying disease progression is a ‘cure’.”

When asked whether patients should take this nutrient, Mahajan emphasized, “We do not recommend patients use over-the-counter ɑ-ketoglutarate to self-manage their disease. We fed our mice very high doses and there were significant side effects. Our efforts are now shifting to find the right ɑ-ketoglutarate therapy that patients can take safely.”

The findings were described in a manuscript, “Metabolite therapy guided by liquid biopsy proteomics delays retinal neurodegeneration,” published in The Lancet’s EBioMedicine.

Mahajan, director of the Stanford Molecular Surgery Program and vice chair of ophthalmology research, added, “Identifying unique biomarkers from the earliest to the latest stages of retinal disease, and then using metabolites linked to those biomarkers is an exciting approach. Catching the disease in its earliest stage is crucial to delaying photoreceptor death, and that means catching the disease at the molecular level.”

Currently, clinic exams can only reveal the disease after damage to the retina has occurred, but molecular analysis may allow researchers to observe depleted rod phototransduction proteins in the retina and elevated within the vitreous before significant loss of the photoreceptor cell nuclei is detectable by histological analysis.

In human patients, liquid biopsies could similarly be used as an early diagnostic to confirm the onset of photoreceptor degeneration, even without diagnosis of a specific genetic mutation by genetic testing.

Mahajan said, “It’s really important for us to develop therapies for the many patients that don’t have a known gene, despite extensive genetic testing. They are not eligible for gene therapy, but they still need a therapeutic plan.”

This approach has many applications. It may be possible to use this liquid biopsy approach to estimate the molecular stage of disease based on the proteomic content of the vitreous. Comparison of proteomes before and after therapeutic approaches can also be studied using liquid biopsy and may have important implications in gene therapy studies.

Based on his lab’s success in identifying protein biomarkers and using targeted therapies to fight eye disease in mice, Mahajan established the Stanford Molecular Surgery Program and an ophthalmology biorepository.

The biorepository links the research lab with the operating room, creating the perfect conditions for translational research aimed at finding new clinical treatments for patients with hard to treat and incurable eye conditions.

Mahajan said, “With this research validation in mind, we are working to acquire the personnel, instrumentation, and analytic systems to expand the biorepository to all areas of eye disease at the Byers Eye Institute.”

Authors of “Metabolite therapy guided by liquid biopsy proteomics delays retinal neurodegeneration,” published in EBioMedicine include: Katherine J. Wert, Gabriel Velez, Vijaya L. Kanchustambham, Vishnu Shankar, Lucy P. Evans, Jesse D. Sengillo, Richard N. Zare, Alexander G. Bassuk, Stephen H. Tsang, Vinit B. Mahajan.